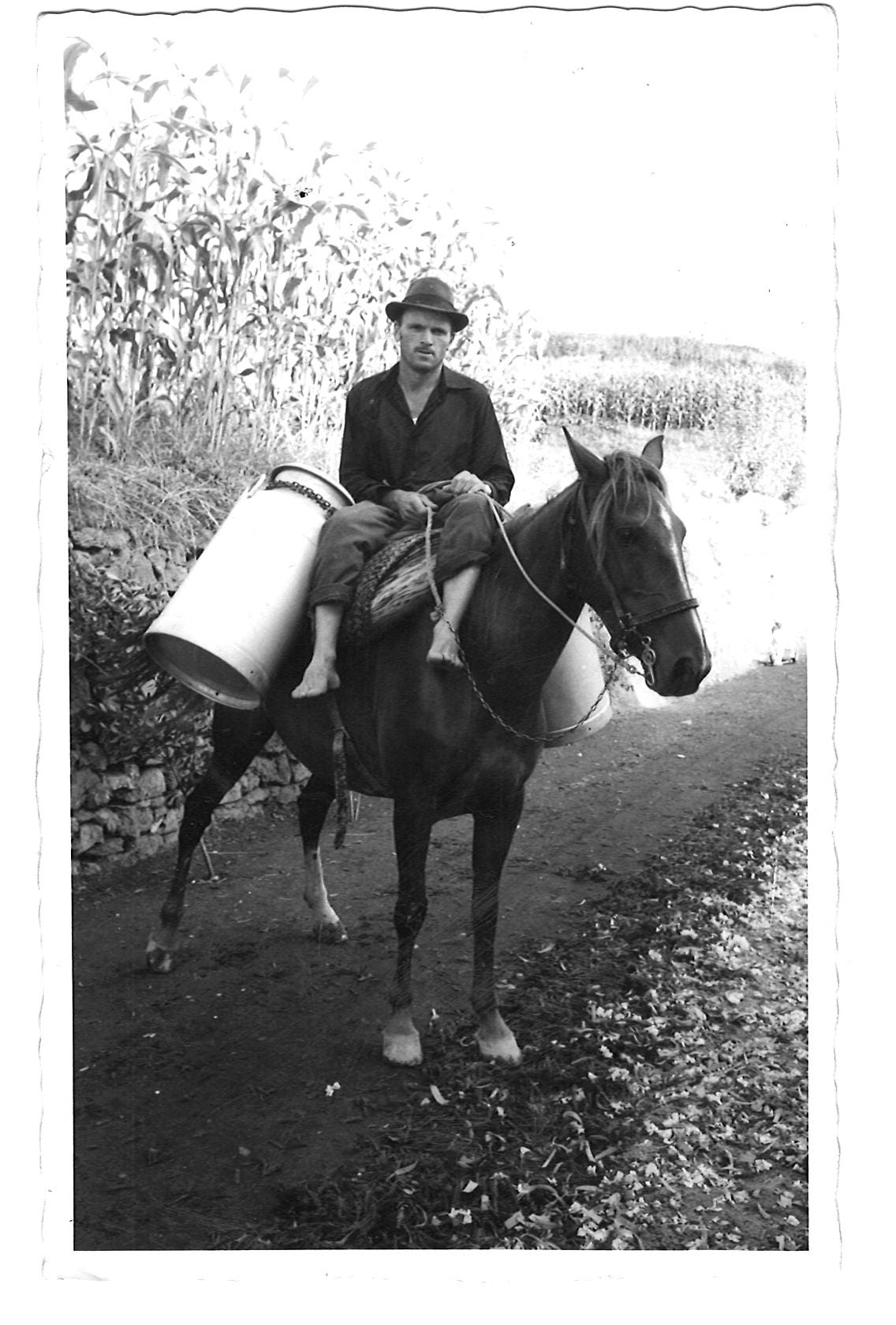

There’s a photograph of my uncle Mariano I keep tucked in the back of an old album—creased down the middle, faded to a brownish hue, like it spent too much time in someone’s back pocket. He sits on his horse, milk jugs danging from the animal’s sides. It was taken in Lomba da Maia, wearing a black shirt, sleeves rolled, hands loosely holding onto the reins. He’s not smiling. He doesn’t need to. The look on his face says everything. It’s the expression of a man who stayed behind.

Mariano was the youngest of my father’s brothers. My father, a serious man who left São Miguel for the iron lines of CP Rail before trading it in for the bricked factories and narrow alleyways of Toronto’s west end, had long since shed his island skin. He arrived in Canada with a suitcase tied with string and a set of promises folded in his coat pocket—one for each of his siblings. He would bring them all over, he said. Give them a better life. And for most, he did.

Except for Mariano.

It’s not as though my father didn’t consider it. I remember the whispered conversations at the kitchen table, the ones I wasn’t supposed to hear. Late nights when my mother would boil chamomile and Dad would lean forward, voice low and urgent.

"Ele não vem." He won’t come.

"Porque não?" Why not?

"Porque a Maria… ela não aguenta aqui. É outro mundo." Because Maria... she wouldn't survive here. It’s another world.

Tia Maria. Sweet, slow-speaking Maria who never raised her voice and stirred her soup the same way she stirred her thoughts—carefully, cautiously, as though afraid too many stirs might bring something to the surface she couldn’t handle. My father said she didn’t have the “cabeça” for Canada. Couldn’t handle the cold, the pace, the invisible rules you only learned when you broke them. He believed that even if Mariano made it here, he would never bring her and the children. That he would get stuck between two lives, and that none of them would be better for it.

Still, there was more.

Someone had to stay behind. That was the unspoken pact—one brother would remain to tend to the land, care for the stone house with its chipped blue shutters, the fig trees in the yard, the inheritance left behind like a fragile bird’s egg in a nest. My father, in his careful logic and deep loyalty, gave that task to Mariano. Maybe he thought it was an honour. Maybe he thought it would be a way for Mariano to belong to something bigger than poverty.

But perhaps, it was a sentence. A quiet exile masked as responsibility.

I only knew Mariano through that one visit when I was twenty-one—that surreal trip back to the island that smelled of sea salt and cow dung. A trip that felt like walking into someone else’s memories. We’d arrive, Canadian and strange, with our nylon suitcases and our big city shoes. Mariano would greet us at the door, arms outstretched, cheeks rough with stubble. His voice caught when he saw my mother and me. The youngest greeting the progeny of the eldest. The one who stayed, greeting the family of the one who left.

He’d take us around the property. Show us the stone wall that needed fixing. The plot of land where the corn used to grow. His words were always a little defensive, like he was trying to explain a math problem that didn’t add up. As a child, I didn’t understand it. But I felt it—something unspoken and bruised between him and my father.

He had entrusted Mariano with a legacy. And perhaps, somewhere along the way, that trust had frayed.

After my father died, we went back to settle the affairs. It was a journey threaded with grief and the quiet, grinding business of closing chapters. And that’s when the truth spilled out—not all at once, but in bits and stammered confessions. Mariano had sold land that didn’t belong to him. Pocketed money. Spent what should have been shared.

The air in that kitchen was heavy the day it came out. Mariano stood in the doorway, aged a decade, his eyes rimmed red. He wept. Not like a man caught in a lie, but like a man who had run out of ways to explain himself.

He said he did what he had to do. That the land was failing. That no one else was coming back. That he had no choice. But maybe he did. Maybe that’s the tragedy of it.

The true extent of what he took, we’ll never know. The money, the land, the decisions made behind closed doors. It doesn't matter anymore. What I remember is my mother—my mother, who had every reason to walk away, reached into her purse and handed him an extra five hundred euros.

She placed it gently on the table, as though it were not money, but something softer. A mercy. A peace offering from a life he never got to live.

Sometimes I wonder what would’ve happened if my father had brought him over. If Mariano had landed in Pearson Airport with a crumpled coat and dreams too big for a suitcase. Would he have found work in a cannery in Etobicoke? Learned how to drive in the snow? Would Tia Maria have withered in the winter or bloomed in ways none of us could have predicted?

Maybe that’s the cruel question of the immigrant story—the alternate versions of our lives that might have been. My father chose for all of them. He chose the life of asphalt and maple trees for the ones he thought could survive it. He left Mariano behind, thinking he was preserving something. But time doesn’t preserve, it erodes. And responsibility, when unequally given, can curdle into resentment or greed.

Still, I don’t believe my father stopped loving him. If anything, I think he mourned him while he was still alive. That quiet mourning you carry when you know a choice you made—however practical—left someone you loved stranded.

That is the story of many families. One foot in the old world, one in the new. And in between, a brother who stayed behind.

So many gorgeous lines in this piece! So artfully crafted. Bravo!

Beautifully written, Anthony.