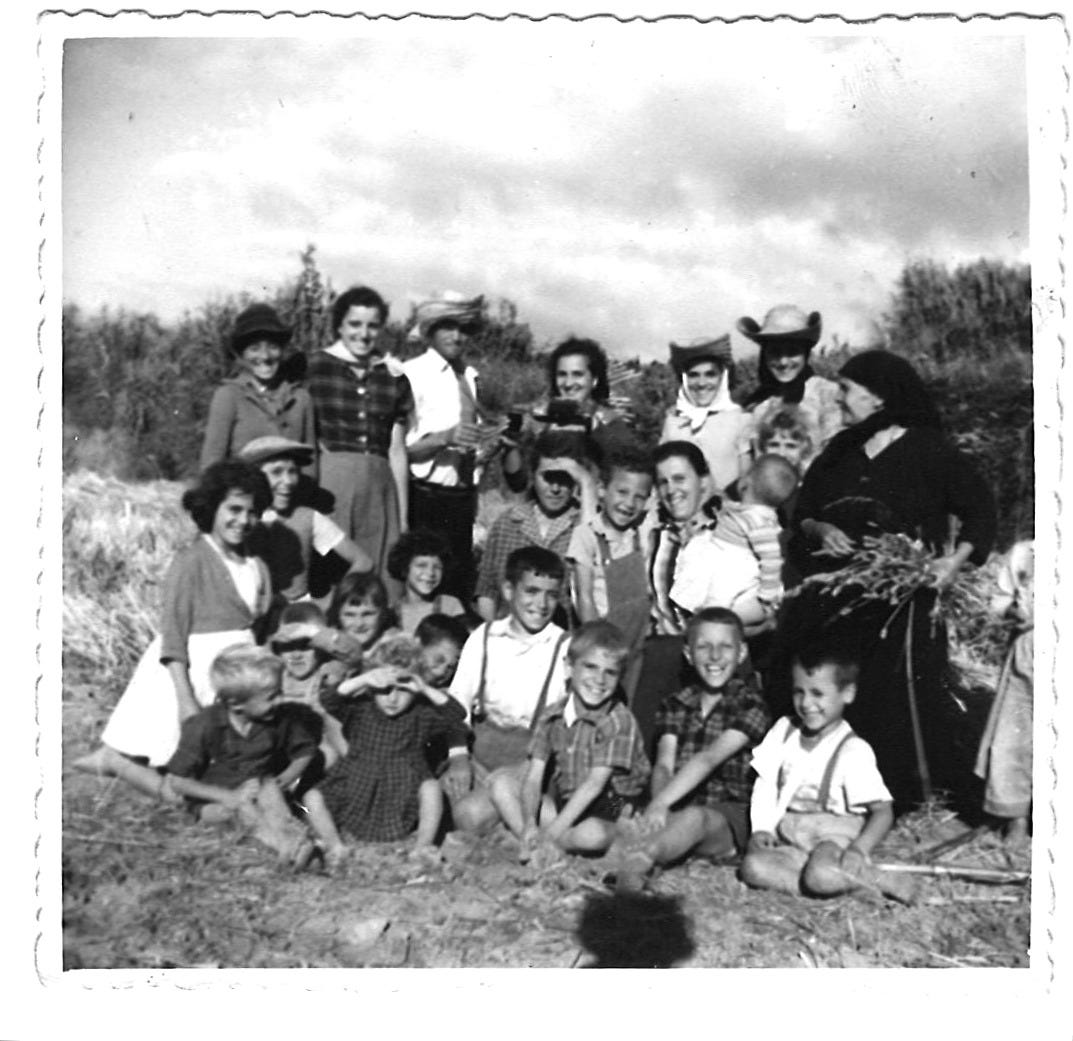

When I was a boy, Sundays smelled like roast chicken. We used to make the one hour drive from our house on Palmerston Ave in Toronto to pack into my Uncle Joe’s house in Hamilton, shoes stacked by the door, jackets slung over the stair banister, someone always laughing too loud in the kitchen. My Uncle Joe and my dad would slap each other’s backs like they were trying to burp old grudges from their bones, and the sisters—My Tia Albina and Tia Candida—would often be there, as well. They’d hover near the stove with their arms folded or over the Sunday table setting, commenting on everything and nothing. My Tia Lourdes, Uncle Joe’s wife and the kindest and gentlest soul, along with my mother would navigate things for the siblings and the family they married into. All the cousins varying in ages would burst through that front door or out back and we played games, the older ones choosing to talk or preen. It was noise and it was warmth, and it was ours.

But those days live in a part of me now that feels amputated—phantom-limbed. Somewhere between nine and ten, I began to notice the silences. They crept in like stains—first small and almost unnoticeable, then blooming, spreading until all that was left was absence. No more Sunday trips to my Uncle Joe’s. Tia Albina and my Uncle Luis moved out because my father asked them to—told them they weren’t welcome any longer. (I was close with my Tia Albina, as was my mother. It was a very painful time). My Tia Candida tried to broker some kind of peace between the siblings, but my father’s drinking meant any temporary truce didn’t hold for long. I didn’t know what it meant back then, only that the air in my house got heavier, that my father’s voice grew louder and less coherent by the end of the night. My parents would argue more and my sister and I would barricade ourselves in our room. Holidays became lonely because my father’s family stayed away, barred from our home—fewer and fewer people came around.

It’s only now, as an adult, that I see it clearly: we lost half our family. And they didn’t die. They just weren’t welcome any longer and slipped away from my reach.