He came in 1955, hands still raw from the difficult work of another country. A boat. A train. Another train. Then the long whine of the rails that would eventually become his temporary home. My father, like so many men with names the foremen never bothered to pronounce correctly, arrived in Canada with a suitcase and the kind of hope that hums inside a man when he doesn’t yet know what he’s up against. That’s what I’d like to think of his first years here; it’s what I can glean from the patchwork of what he once shared with me. I’ve lived with his stories for as long as I’ve lived with his shadow. They came in broken English, rarely in Portuguese, softened by time and memory, drifting over the dinner table like smoke from a fire barely burning. He spoke often of the Rockies. Of the way Lake Louise, caught in a pocket of blue ice and silence, opened his chest like a prayer. Ali, ali eu vi Deus. There, he told me, he saw God. Not in the churches of Lisbon with their gilded altars and mutilated statues. No. In the way light slipped down the mountains and touched the water so gently it felt like a benediction.

But it was the railway that brought him west. Not faith. Not poetry. Just a job.

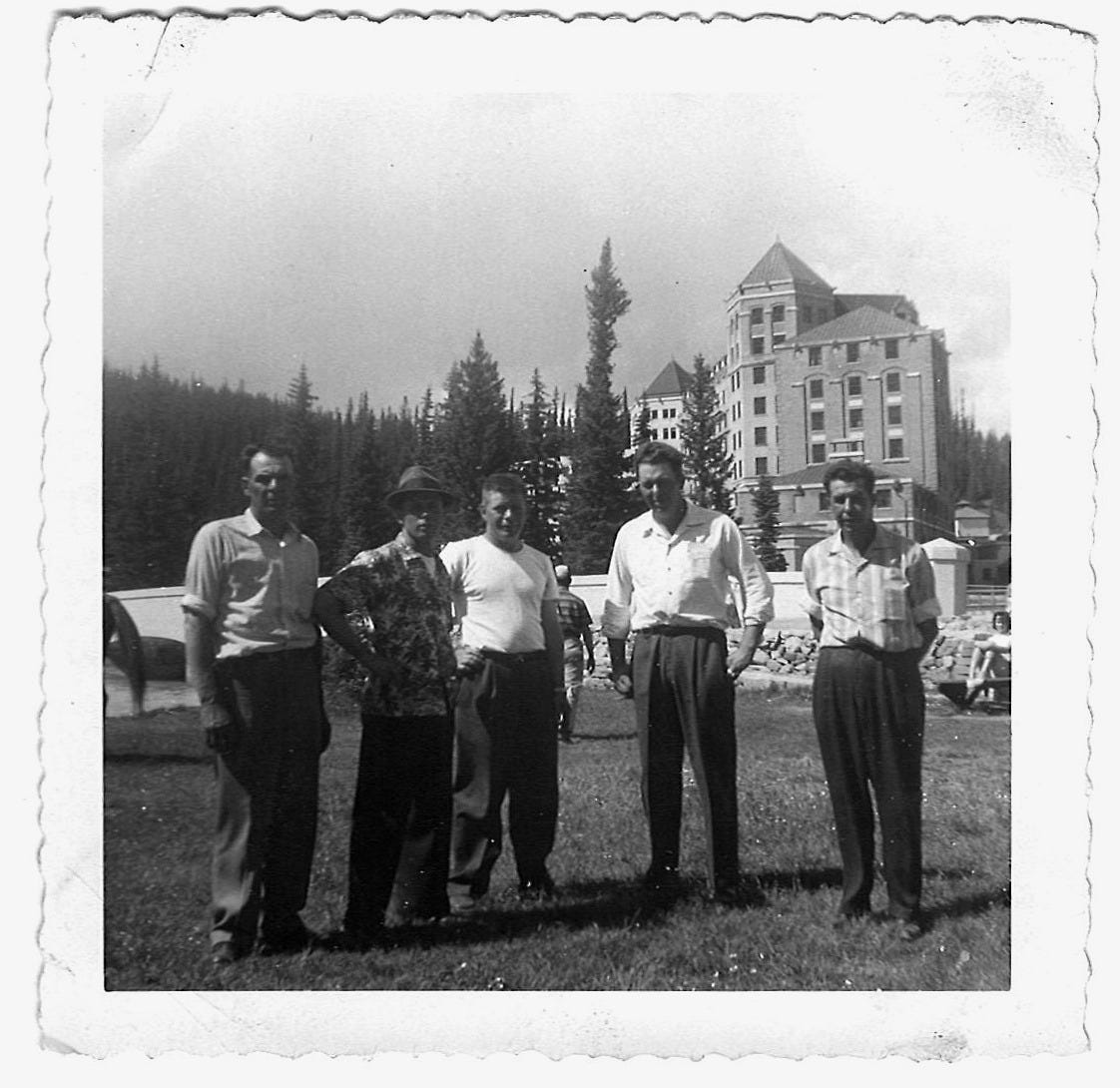

He was one of the homens duros—the hard men—who lived in bunk cars for the weeks they worked the line, washed with cold water from cracked enamel basins. They cooked sardines over tin stoves, drank vinegar-red wine from tin cups, and folded their futures into narrow steel beds at night, their backs screaming from the day's labour. He said there were dozens of them: Portuguese, Italians, Poles. A tower of Babel rattling down the rails. They were men who couldn’t speak to each other in words but knew the rhythm of a pickaxe, the whirring grind of metal tracks, and the whistle of a foreman’s impatience. They’s be out for five or six weeks before returning home to Kenora, where they were stationed. A rest of a few days before the next trip out. My father said he was never happier—something of the bond he felt with these other men, living and working together under the natural canopy that was Canada. It was work, but it was also freedom.

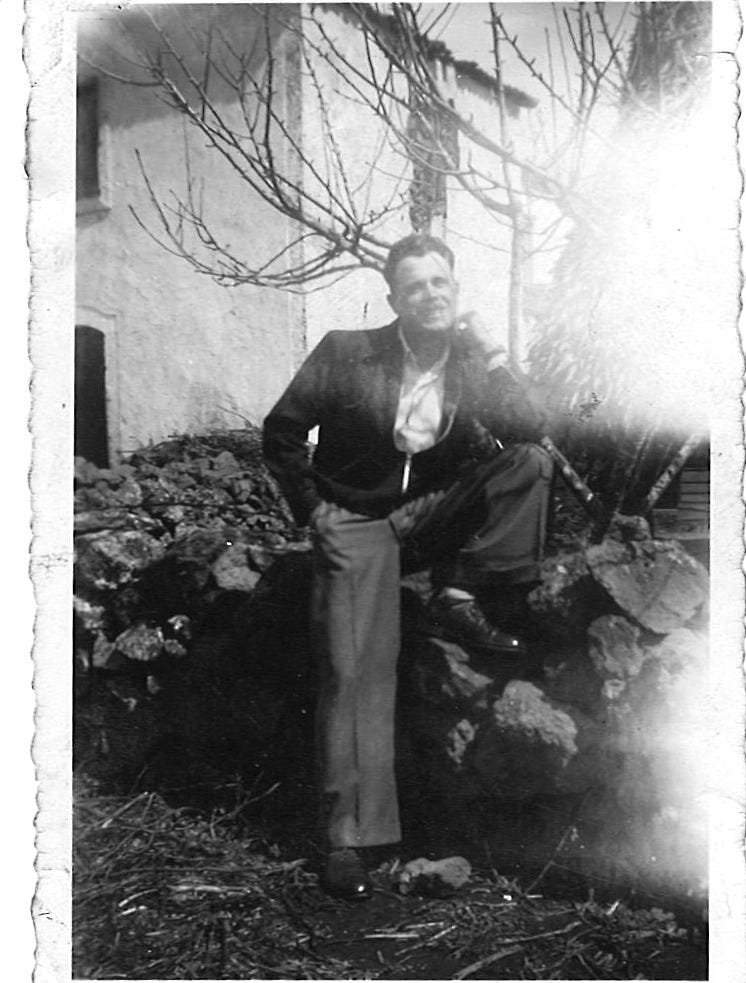

When I was a boy, I used to imagine my father standing on the tracks, shoulder to shoulder with other men like him, the kind whose dreams had been flung over an ocean and nailed down into steel. I imagined him younger, his face not yet hardened by time or disappointment, with fair hair beneath a toque and blue eyes that squinted against snow-bright skies. I liked to think of him filled with fire, with purpose, with the kind of belief that maybe he could carve out a new world not just for himself, but for a family that didn’t yet exist.

But now, as a man myself, I wonder what he saw when he stepped into this country. What the first breath of Canadian air felt like in his lungs. If he mistook it for freedom. If he mistook it for something kinder than it turned out to be. I also wonder what he would make of Canada and the world right now, if he were still alive.

He said the work was endless. You woke before light, and you didn’t stop until the sun slid down behind a ridge of spruce and the air turned to glass. Shoveling gravel, hauling ties, tamping ballast. Steel in your hands, steel in your spine. He told me they used to joke that you became the rail you worked on—that your bones grew iron, that your skin rusted in the rain. But when he said it, there was never any laughter behind the words.

The West, though—that was different.

Revelstoke. He said it like it was a secret. A sacred place nestled between storms. He spoke of elk drifting like ghosts through morning fog. Of silence so complete it rang in his ears. Of the snow, not as something that buried you, but something that made everything cleaner. I think that’s what saved him, in those early years. Not the job, not the cheque in the envelope at the end of the month. But the wild. The staggering, unnameable beauty of a place untouched by ambition or progress. Nature, vast and unmoving, offering something that resembled comfort. He used to say that the mountains made a man feel small, and that was a good thing. Because when you're small, you know your place. You learn to listen. Every time he’d say the word Revelstoke, Banff, or Lake Louise in his marbled Portuguese, my sister and I would giggle a bit, try not to laugh when we lost our father to the memories of that time and place he had left behind. It’s terrible when I think of how dismissive we were of his stories. We were only kids.

Now, as an adult, I see those stories in a different light. Hope is a slippery thing. It doesn’t die all at once. It sheds itself slowly. I’d like to think my father held onto it for as long as he could. Carried it like a talisman in his coat pocket. But the seasons in the West were long and punishing. The isolation chewed at him. The men rotated in and out. Some never returned. Some fell into drink. Some into silence.

And something in my father began to shift.

He never talked much about the cost if it all. Not the smashed fingers or back spasms he was plagued with. Not the cough that would ride his chest every winter for the rest of his life. But I would see him sometimes, shirtless, in the basement, and although he had no visible scars, I imagined they were there. Those scars told stories he never spoke. I used to picture one along his forearm, a clean slice where a rail had slipped loose. Another on his knee, raised and red like a burned rope. Childhood imaginings, yes, but perhaps they were my way of making my father into a hero. His body bore the country before his heart ever did.

He came to Canada thinking he would be made new. That this country would be a rebirth. Renascimento, he called it once. And maybe it was. But not in the way he had imagined. The man who returned to Kenora with a wife after those six years on the rails was harder. He settled in Toronto and got a job at St. Michael’s Hospital in their housekeeping department. The nuns at the hospital adored my father and he quickly made a life for himself and his wife and his children in the big city. He became quieter. He had learned that this country doesn't bend to your will. You bend to it. Or you break.

He worked the lines, and they worked him.

Still, he brought pieces of the West home with him. Many of these pictures I’ve been sharing with you were cherished, kept in a solid box layered with tissue paper. A tattered black-and-white photograph of Lake Louise was taped inside our family bible. And my father was not a religious man. I’ve never been able to find that family bible. Before the drink took hold of him, he had a fondness for silence, for long walks in the woods, for the way wind moves through pine. And he carried stories—some half-finished, some too painful to end.

I think he believed that one day he would return. That he’d go back not as a labourer, but as a man who could afford to simply look. But life got in the way. Kids. Mortgages. A shift at the hospital that started at 5 a.m. A back that no longer did what he asked of it. The Rockies would have to be a bookmark in his memory. A sacred geography he mapped again and again in his telling. In the way his eyes softened when he said "Revelstoke." In the hush of his voice when he recalled Lake Louise, its water still and bright like a held breath.

Now, I look through these photographs and sit with these stories and try to find the man inside them. The young one. The one with too much hair and not enough English. The one who arrived with his best shirt folded beneath a tin of sardines. Who stared up at the mountains and felt something holy stir inside him. I will never know exactly what he hoped for. He never said. Hope, for men like him, was private. Kept close to the chest, away from the wind. But I know what was left behind. I know what took its place. A steady resolve. A quiet ache. The knowledge that even in beauty, there is loneliness.

And yet—he gave us this country. Not the version you find in postcards or tourism ads. But the one he bled into. The one he held onto. The one that gave him just enough to stay. The rail lines he helped lay are still there. Steel bones across a vast and sprawling land. I sometimes think of him out there, young and lost and full of dreams. The sky wide. The trees tall. And beneath it all, my father, listening to the sound of a train disappearing into the distance, hoping it was going somewhere good.

You have such a gift for storytelling, Anthony. You sweep us up in your tales; we are there witnessing those places and people in the flesh. Thank you for this poignant piece of your family history

Wow Anthony!

Beautiful story. It brought tears to my eyes…