I was 18 when my father passed. Fourteen years later, at the age of thirty-two, I visited his grave for the very first time.

It was a quiet morning in Prospect Cemetery. The sun filtered gently through the thinning branches above, and the spring air still held a soft chill. I brought a small bouquet of flowers in one hand and a prayer candle in the other, my steps tentative as I approached the place where my father had been buried for over a decade. I visited the cemetery a few times each year to spend some quiet time by my mother’s grave. I always drove by my father’s plot (they aren’t buried together) but would never get out of the car. Not for his birthday or All Souls Day. Not for Christmas or anniversaries. Not for anything. But that day, Father’s Day 1999, something shifted in me. I had become a first-time father myself the previous fall, and everything about that role—its weight, its joy, its complexity—was pressing heavily on me.

I’m not ashamed to say it . . . that visit wasn’t for him; it was for me. And it was for my first son, Julian.

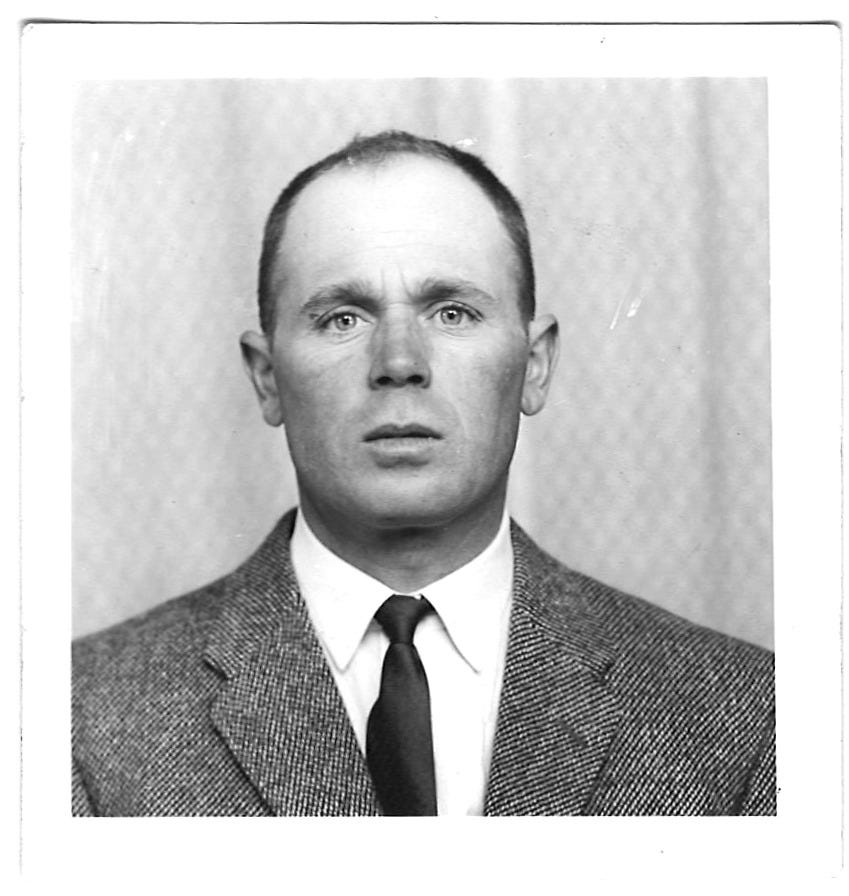

My relationship with my father had always been difficult. Tumultuous is the word I use. He was a hard man—quick to anger, emotionally closed off, and steeped in a traditional view of masculinity that left little room for vulnerability. Our home was filled with silence and expectations. Love was rarely spoken, and rarely shown the way I wanted it to be. I carried those years like stones in my pockets, silently, convinced I had moved on.

But when I became a father, those old feelings came rushing back. Every time I doubted myself—every time I felt afraid that I wouldn’t measure up—I thought of him. I wondered if he had ever felt this way, too.

One moment I often return to is from when I was about seventeen. I had received two acceptance letters around the same time—one from OCAD, the Ontario College of Art and Design, and the other from the University of Toronto. I had always known I wanted to work in the arts, to make something that lived beyond the page, beyond the moment. OCAD was where my heart wanted to go. But I didn’t tell anyone. I hid that letter under my mattress, letting it sit there like a secret dream I wasn’t sure I was allowed to have.

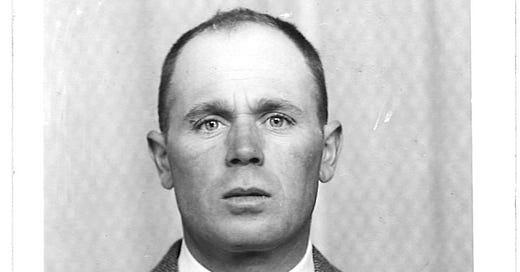

Instead, I brought the University of Toronto letter downstairs to my father. I remember the way he looked at the envelope—how his eyes locked on the university’s crest, that stamp of approval society seemed to value so much. He didn’t say a word at first, just opened it and read the first few lines. And then I saw it: the swelling in his eyes, the emotion he couldn’t quite contain. My father, the man who never showed weakness, was holding back tears. Before he could say anything—before I could hear whatever it was that was building in his throat—I turned and walked back up the stairs. I convinced myself that I had done the right thing, kept saying it over and over in my head, never out loud. That making him proud was worth the sacrifice. But part of me always wondered if he somehow knew about the other letter. If he would’ve been proud of that, too. I wonder, too, what he would think of my career as a writer and more importantly, what I find myself turning to when I do sit down to begin a story.

I beginning to see the world and my place in it from a different lens. Over time, parenthood strips away your illusions. It humbles you. And in the early days, as I paced the floors at night or sat with my boys’ sleeping on my chest, I started to think less about the father I wanted to be—and more about the father he had tried to be, in his own flawed way. That made me angry, but it also made me realize that I couldn’t fully embrace this new role without confronting the past. I couldn’t parent freely with all that unresolved pain clinging to me. That’s what brought me to the cemetery. There was no ceremony, no dramatic overture. Just me, a candle, some flowers, and a heart full of complicated emotions. I stood there and allowed myself to feel everything: the hurt, the confusion, the longing, and yes—the love, buried under all that silence.

And maybe, in some way, that’s how I honour him, too. Becoming a father cracked something open in me—some hidden chamber I had walled off for most of my life. Holding my child for the first time, feeling that tiny, fragile body curled into mine, it was as if a key had turned. The love was overwhelming, yes, but so was the fear. The responsibility. The hope. And with all that came memories—painful, sharp-edged memories of my own childhood, and the man who had shaped so much of it.

Now, as a father, I still make mistakes. My kids will call me out on it. There are days I’d lose my patience. Nights I doubted myself. But there is also deep, breathtaking joy: the way they now laugh together, the way they once reached for my hand, the way they’ve grown to trust me. And there's a promise, too: that I will do my best to love them without condition. That I will be open. That I will listen and I may even add a suggestion or two. Sorry boys, that’s part of parenting. I will try, always, to be better, even when it doesn’t feel that way.

Forgiving my father was not about excusing what he did or didn’t do. It wasn’t meant to erase the difficult things I went through as a boy—to me, to my sister, but most importantly, to my mother who stood by him, even when we asked her to leave. Your father is my cross, she’d say. It was about acknowledging his humanity. Seeing him not just as the man who raised me, but as an imperfect man—as all of us are—with fears, doubts, dreams, and limitations of his own. And in doing so, I found space to grow. To breathe. To love more fully.

That day at the cemetery, I didn’t just forgive my father. I said goodbye to a version of myself that had carried pain for too long. I gave myself permission to heal. To lead with compassion instead of resentment. I’m excited and proud to celebrate the independent and individual men my three sons have become. I love them like I’ve never loved. When I hug them on Sunday for Father’s Day, I will be overwhelmed with the hope that lies in their embrace. And I will think of my own father, imagine embracing him fondly. And perhaps wondering, in some strange way, this was how things were meant to unfold for me. No anger or hurt or resentment. No regrets . . . just a little bit of lost time.

Another beautiful dedication to the power of love. Thanks for sharing, Anthony.

I was very touched by your revelations.